AlphaGo and AlphaGo Zero

Introduction#

In 2016, the AlphaGo program developed by DeepMind defeated Go World Champion Lee Sedol in a five game match, a landmark achievement in the history of Artificial Intelligence. About a year later, Deepmind introduced AlphaGo Zero, a markedly stronger Go program trained without supervision from any human games. In this post, I will cover the internals of these two systems. I assume familiarity with the basic setup, terminology, and notation of reinforcement learning.

Why is Go hard?#

For the purposes of understanding the AlphaGo family, only the basic parameters of the game of Go are important. Go is a two player, deterministic, perfect information, abstract strategy game played (in professional play) on a $19$ by $19$ grid. Players alternate placing black and white stones on this grid, aiming to surround more territory on the board than their opponent. The most relevant distinguishing feature of Go among similar games are its extremely high branching factor and length. While a typical branching factor for a game of Chess is $35$, Go games generally have hundreds of possible moves in each position and last for twice as many moves. This makes the relatively simple search techniques that yield superhuman play in Chess insufficient for reaching the level of a strong amateur in Go.

Monte Carlo Tree Search#

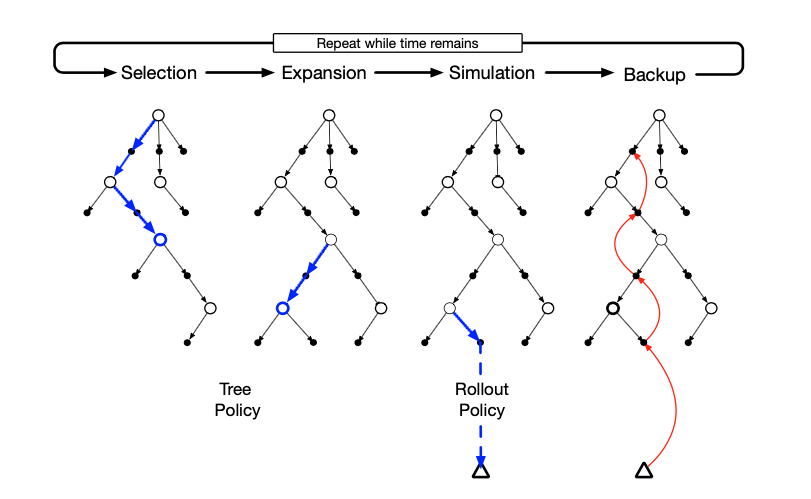

Use of the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm was responsible for Go programs reaching the skill of a strong, but not top-level human prior to AlphaGo. It is a decision-time planning algorithm which uses a model of the environment (in this case the game of Go) to improve upon decisions made by a policy $\pi$, generally called the rollout policy. Asymptotically, it converges to the optimal policy and value function. It initializes a tree of state nodes, starting at the current state if the tree is empty. Each tree node maintains visit counts and action values $Q(s, a)$ as part of the search process. The tree is expanded and evaluated by iterating through four stages: selection, expansion, simulation, and backup.

|

|---|

| Monte Carlo Tree Search, from [3] |

Selection#

Selection traverses the tree from the root to a leaf node by following a tree policy, commonly $\epsilon$-greedy or UCB using the stored action values. The tree policy should sufficiently explore the states immediately following the root state, while eventually improving on the rollout policy within the tree because it exploits the empirical returns of the Monte Carlo simulations.

Expansion#

Expansion expands the search tree by adding some amount of children from the leaf node traversed to in Selection. The frequency that the tree is expanded and the number of child nodes added varies with different implementations of the algorithm.

Simulation#

Simulation evaluates the last reached node (either the leaf or an added child) using the rollout policy $\pi$. It does that by following $\pi$ until the end of the episode is reached. Note that it is not even necessary for the rollout policy to be close to optimal for MCTS to be effective, though of course it does not hurt.

Backup#

Backup updates the internal state of the tree using the return(s) from the simulated episode. In most cases this simply entails incrementing the visit count for each visited node and adding the return(s) to the running average of each node’s action value function.

AlphaGo#

A common approach taken by strong computer Go programs prior to AlphaGo was to train a policy to predict expert human moves, then use that policy in MCTS. AlphaGo takes a similar approach, but uses pipeline of several deep convolutional networks in the MCTS instead the shallower models common in earlier efforts.

Supervised Learning#

AlphaGo uses two policies trained by supervised learning, which they refer to as the “Rollout policy” $p_{\pi}$ and the “SL policy network” $p_{\sigma}$. Both are trained to predict expert human moves using millions of positions from an online Go server, augmented by including all 8 symmetries of each position. $p_{\pi}$ is quite similar to the policies used in prior Go programs in that it is a linear model trained on human-designed features. It is intended to guide the MCTS simulations, so fast inference (2 $\mu$s vs 3 ms for the neural networks) was prioritized over accuracy. $p_{\sigma}$ is a 13 layer convolutional neural network that achieved what was at the time state of the art test classification accuracy on the dataset used.

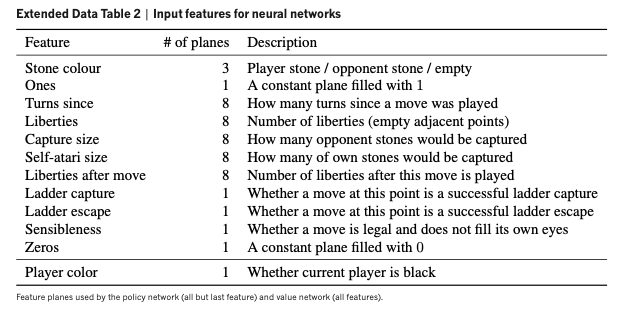

The input to the SL policy network, as well as the other two networks trained later in the pipeline, is a set of $48$ $19$ by $19$ feature planes encoding the game position as well as some basic Go knowledge.

|

|---|

| Feature Planes for the AlphaGo Neural Networks, from [1] |

Reinforcement Learning#

The next step of the pipeline trains a “RL policy network” $p_{\rho}$ by fine-tuning $p_{\sigma}$ using policy gradient reinforcement learning and self-play. $p_{\rho}$ is trained by playing games against previous iterations of itself instead of its current iteration to prevent overfitting to the current policy. Given a game with outcome $z = \pm 1$, the network weights are updated according to REINFORCE: $$ \Delta \rho \propto \frac{\partial \text{log }p_{\rho}(a_t | s_t)}{\partial \rho}z $$ Using just the fine-tuned policy $p_{\rho}$ and no search led to play of comparable or greater strength than the top Go programs available at the time.

Value Network#

The final network is trained to approximate the value function $v^{\rho}(s)$ of the RL policy network. This is done via supervised learning, with the value network taking a position from a RL policy self play game and predicting the outcome $z$. Weights are updated by stochastic gradient descent on the MSE: $$ \Delta \theta \propto \frac{\partial v_{\theta}(s)}{\partial \theta}(z - v_{\theta}(s)) $$ An important implementation detail is that each training example is taken from a distinct game, as successive positions from the same game are highly correlated and lead to overfitting.

Bringing it all together with MCTS#

AlphaGo brings together the trained networks into a complete system using MCTS. As is standard, each node in the search tree maintains a visit count $N(s, a)$ and an estimated action value $Q(s, a)$. In addition, each node stores prior probabilities $P(s, a)$, which are output by the SL policy network $p_{\sigma}$ when the node is expanded in the search. Notably, the SL policy is used to compute the prior probabilities instead of the stronger RL policy, as this surprisingly lead to empirically stronger play. The authors of AlphaGo hypothesize that this is due to the SL policy selecting a more diverse beam of moves. The tree policy initially defaults to using the prior probabilities to guide search, but over time lends more weight to the action values estimated through the Monte Carlo simulations: $$ \begin{aligned} a_t = &\text{ argmax }(Q(s_t, a) + u(s_t, a)) \cr \text{where } &u(s, a) \propto \frac{P(s, a)}{1 + N(s, a)} \end{aligned} $$

Evaluation of the leaf nodes is slightly non-standard in that is done using both the result of a simulation $z_L$ and the value network: $$ V(s_L) = (1 - \lambda)v_{\theta}(s_L) + \lambda z_L $$ In practice a balanced mixture $\lambda = 0.5$ yielded the strongest play, suggesting that is important to balance the more precise evaluation of the weak rollout policy via simulation and the less precise evaluation of the strong RL policy using the value network. At the end of search, the action with the highest visit count is selected.

Combining the networks in this fashion creates a player of markedly greater strength than any system prior, with AlphaGo winning nearly 100% of its games in a tournament against the strongest available Go programs. AlphaGo at this stage was strong enough to defeat European Champion Fan Hui 5-0 in an October 2015 match.

AlphaGo Lee#

The published version of AlphaGo differs slightly from the version that beat Lee Sedol in 2016. The main differences are that the size of the input was scaled up, using $256$ feature planes instead of $48$, and that the value network was trained to predict the value of positions as played by AlphaGo instead of by the RL policy network. This creates a iterable policy improvement algorithm, where successive versions of AlphaGo can be trained by learning a value network corresponding to the previous iteration. This is a step in the direction of improvement via pure self-play, which is the approach taken by AlphaGo Zero.

AlphaGo Zero#

AlphaGo Zero eschews the complex pipeline of networks used in AlphaGo for a single network trained purely on board positions by self-play. It turns out this architecture is sufficient to not only exceed human skill in Go (and later in other games such as Chess & Shogi), but also yield superior play to MCTS based on human supervision. This is despite the fact that AlphaGo Zero has no knowledge of human play or human-designed features encoding common sense strategy. Instead, AlphaGo Zero develops its strategy organically through a combination of re-discovering human Go knowledge and developing previously unknown strategic concepts.

Network Architecture#

AlphaGo Zero uses a single convolutional neural network with 39 residual blocks. The input is a stack of $17$ $19$ by $19$ feature planes which encode the positions of each player’s stones in the last $8$ positions, as well as a constant plane indicating whose turn it is. Position history is needed because Go is not fully observable, with repetitions being forbidden. The network serves as both the policy and value function, with outputs $(\vec{p}, v) = f_{\theta}(s)$ of $p_a = \mathbb{P}_{\pi}(a | s)$ for each action $a$ and $v = v^{\pi}(s)$.

MCTS Training Algorithm#

Self-play proceeds using MCTS, with the same tree policy as AlphaGo, however rollouts are omitted in favor of simply using the value network to evaluate leaf nodes. After 1600 iterations of MCTS, a move is seleted proportional to an exponentiated visit count for the children of the root node: $$ \pi_a \propto N(s, a)^{1 / \tau} $$ where $\tau$ is a temperature controlling the amount of exploration the search does. A game of self play with result $z$ provides datapoints $(s_t, \vec{\pi}_t, z)$ for $t \in [0, T]$. The training algorithm samples from these datapoints and performs gradent descent on the loss $$ l = (z - v)^2 - \vec{\pi}^T\text{log }\vec{p} + c||\theta||^2 $$ This has the effect of adjusting $v$ to more accurately value each state, and $\vec{p}$ to more closely match $\pi$, along with L2 regularization.

Results#

Within 36 hours of training, AlphaGo Zero outperformed AlphaGo Lee in terms of Elo. After 72 hours, AlphaGo Zero defeated AlphaGo Lee in 100 straight games at the same time control that AlphaGo Lee defeated Lee Sedol. The authors of AlphaGo Zero isolate self-play reinforcement learning as the key element that allows the agent to achieve such strong results. While the architectural differences were useful, with a supervised learning agent using AlphaGo Zero’s architecture achieving state of the art prediction accuracy on the human Go dataset, this agent still dramatically underformed its self-play trained analogue. This result is highly encouraging, as it suggests that pure reinforcement learning approaches are capable of achieving state of the art results in highly complex domains where human supervision may not be available.

References#

[1] Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. J., Guez, A., Sifre, L., van den Driessche, G., Schrittwieser, J., Antonoglou, I., Panneershelvam, V., Lanctot, M., Dieleman, S., Grewe, D., Nham, J., Kalchbrenner, N., Sutskever, I., Lillicrap, T., Leach, M., Kavukcuoglu, K., Graepel, T., & Hassabis, D. (2016). Mastering the game of go with deep neural networks and Tree Search. Nature, 529(7587), 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961

[2] Silver, D., Schrittwieser, J., Simonyan, K., Antonoglou, I., Huang, A., Guez, A., Hubert, T., Baker, L., Lai, M., Bolton, A., Chen, Y., Lillicrap, T., Hui, F., Sifre, L., van den Driessche, G., Graepel, T., & Hassabis, D. (2017). Mastering the game of go without human knowledge. Nature, 550(7676), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24270

[3] Sutton, R. S., Bach, F., & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT Press Ltd.