Solving Poker using Counterfactual Regret Minimization

Introduction#

Extensive games with imperfect information are a game theoretic model used to represent sequential decision making in situtations involving other, potentially adversarial, agents with differing knowledge of the game state. This is a natural way to model many problems in domains of practical interest such as cybersecurity and auctions, as well as many commonly played recreational games, such as Poker. Research into playing game-theoretically optimal Poker has driven much of the state of the art in extensive game research due to the game’s prominence and difficulty. The huge game tree size of the most common Poker variations poses a significant challenge for computer play, requiring the development of many novel techniques to compress and approximate the game equilibrium. This post will cover the game theory concepts used to model Poker and its optimal play, as well as the most prominent algorithm used in computer Poker, Counterfactual Regret Minimization.

Extensive Games with Imperfect Information#

The notion of an extensive game with imperfect information is a theoretical model commonly used for analyzing multiplayer sequential games with hidden information, such as Poker. It is specifically defined as comprising of the following elements:

- A finite set $N$ of players

- A set $H$ of sequences, called histories, such that $\emptyset \in H$, and $H$ is closed with respect to prefixes. If $h \in H$ is not the prefix of any other history in $H$, it is called terminal, and each non-terminal history $h$ has an associated action set $A(h) = \lbrace a: (h, a) \in H \rbrace$. The set of terminal histories is called $Z$.

- A function $P: H \backslash Z \to N \cup \lbrace c \rbrace$, called the player function. If $P(h) = c$, chance determines the action taken after $h$. For each $h$ with $P(h) = c$, there is an associated probability measure $f_c(\cdot | h)$ that determines the probability of each action taken after $h$.

- For each player $i \in N$ a partition $\mathcal{I}_i$ of $\lbrace h \in H : P(h) = i \rbrace$ with the property that $A(h) = A(h’)$ for all $h, h’$ in the same partition. This defines an associated action set $A(I_i)$ for each partition $I_i \in \mathcal{I}_i$. $\mathcal{I}_i$ is called the information partition for player $i$ and each $I_i \in \mathcal{I}_i$ is an information set.

- For each player $i \in N$ there is a utility function $u_i: Z \to \mathbb{R}$.

The key element that represents hidden information in the games studied with this model is the notion of information partitions for each player. Histories that in the same information set for a specific player are indistinguishable with regards to that player, so they are used to represent game states where hidden information differs but public information does not.

Now that we’ve defined games, we can define strategies. A strategy for player $i$ is defined as a function $\sigma_i : \mathcal{I}_i \to p(\cdot | I_i)$, mapping each information set to a probability distribution over potential actions. The set of strategies for a player $i$ is called $\Sigma_i$. A strategy profile $\sigma$ in a multiplayer game is a strategy for each player, and $\sigma_{-i}$ refers to all strategies in a profile except for $\sigma_i$. $\pi^{\sigma}(h)$ is the probability of $h$ occurring if players follow $\sigma$, with $\pi^{\sigma}_i(h)$ being player $i$’s contribution to this probability and $\pi^{\sigma}_{-i}(h)$ defined as expected. We define similar probabilities $\pi^{\sigma}_i(I)$ for information sets by summing over all histories in $I$. Using these definitions we can define the utility of a strategy profile for each player as $u_i(\sigma) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi^{\sigma}} \left[ u_i(h) \right]$. Define $u_i(\sigma_{-i}, \sigma_i’)$ as the expected utility for player $i$ when all other players play according to $\sigma$ and $i$ plays according to $\sigma_i’$.

Nash Equilibria#

The notion of a Nash Equilibrium is perhaps the most important concept in Game Theory. Given a strategy profile $\sigma$, $i$’s best response to $\sigma$ is $\text{br}_i(\sigma) = \text{argmax}_{\sigma*_i \in \Sigma_i} u_i(\sigma_{-i}, \sigma^*_i)$. This is the strategy that maximizes $i$’s utility given that their opponents are fixed to following $\sigma$. A strategy profile $\sigma$ is a Nash Equilibrium if each $\sigma_i$ is $i$’s best response to $\sigma$. If players are following a Nash equilbirium strategy profile, no player has an incentive to deviate from their strategy as they are already maximizing their expected utility with regards to the other players.

Games can have multiple Nash Equilibria, and every finite game will have at least one. In two player games, Nash equilibria are particularly powerful since any player who follows such a strategy is not guaranteed to not lose in expectation to any opponent (beyond loss guaranteed by the intrinsic advantage in game rules). This is not the case in multiplayer games, where if each player chooses a strategy from a set of Nash equilibria, the resulting joint strategy may not itself be an equilibrium.

In practical applications the notion of an approximate equilibrium is useful. A strategy profile $\sigma$ is an $\epsilon$-Nash Equilibrium if $u_i(\text{br}_i(\sigma)) - u_i(\sigma_i) \le \epsilon$ for each player $i$. A common goal when creating agents that play two player games is to find a $\epsilon$-Nash Equilibrium for a reasonably small value of $\epsilon$. Given the above discussion on the optimality of choosing an equilibrium strategy in two player games, this if achieved is usually sufficient for defeating even highly skilled human opposition.

Regret#

The concept of regret is central in online learning problems and is commonly applied to the game theory setting. Informally, in repeated iterations of a game, we define the regret of a sequence of strategies as the total utility lost by using that sequence rather than the optimal fixed strategy in hindsight. Formally, the average overall regret of player $i$ after $T$ iterations of playing a (possibly non-fixed) strategy profile $\sigma^t$ is defined as $$ R^T_i = \frac{1}{T} \text{max}_{\sigma^*_i \in \Sigma_i} \sum_{t = 1}^T (u_i(\sigma^{*}_i, \sigma^t_{-i}) - u_i(\sigma^t)) $$ Given a sequence of strategy profiles $\sigma_t$, we can define an average strategy that encapsulates the average behavior over all timesteps: $$ \bar{\sigma}^t_i(I)(a) = \frac{\sum_{t=1}^T \pi_i^{\sigma^t}(I) \sigma^t_i(I)(a)}{\sum_{t=1}^T \pi_i^{\sigma^t}(I)} $$ There is a natural connection between regret and Nash Equilibria, which is that in a two player zero sum game where both players have average overall regrets of less than $\epsilon$, the players’ average strategy is a $2\epsilon$ Nash-equilbrium. Notably, this means that if we can generate a sequence of strategy profiles with sublinear total regret, in the limit the average strategy of this sequence is a Nash equilibrium. A crucial detail here is that it is the average strategy profile that converges to a Nash equilbrium, not the strategy profile in the limit, which may never converge.

Regret Matching#

Regret Matching is just such an algorithm to generate a sequence of strategy profiles with sublinear total regret. The regret matching algorithm at each time step assigns a strategy profile where actions are taken proportional to the average regret up until that time, compared against a pure strategy of always selecting that action (rather than the optimal strategy as in the above section). This algorithm generates a sequence of strategy profiles with total regret proportional to $\sqrt{T}$, meaning that in the limit the average strategy converges to an approximate Nash Equilibrium.

Regret Matching works when the game being played is represented in normal form, so as a single round game with an associated payoff matrix. In the case of an extensive game this would mean that each player’s “actions” correspond to complete strategies that contain each response to other players’ choices and chance events. In a game with a particularly large game tree such as most commonly played Poker variations, this is obviously intractable, so a number of more advanced techniques are needed.

I’ve created a toy example of regret matching in action for the games of Rock-Paper-Scissors and the Prisoner’s Dilemma, which is available on Github.

Game Abstraction#

|

|---|

| Game Abstraction, from [3] |

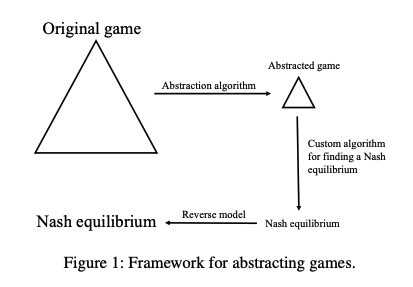

Game Abstraction is a technique to solve for approximate equilibria in large games. The general procedure is to construct a smaller game that is strategically similar to the large game, solve for a small game equilibrium, then transfer that equilibrium back up to the larger game. If the abstracted game is chosen carefully, then the equilibrium found there should still be an approximate equilibrium in the full size game. Game abstractions are selected both by hand using domain expertise as well as by some automated processes. It is generally the case (and logical) that larger abstractions transfer better to the full size game, so developing methods that can efficiently solve for equilibria in large size games is still useful. The general progression of improvements in Poker AIs has been more and more efficient equilbrium finding algorithms which allow larger and larger abstractions of the full Poker game tree to be solved.

Counterfactual Regret Minimization#

Counterfactual Regret Minimization (CFR) is one of the key techniques that allowed Poker abstractions to grow by several orders of magnitude. Rather than applying the regret minimization procedure on a complete strategy for the game, CFR applies Regret Minimization at each information set. Since Regret is a notion defined over a complete strategy, we need to define an analogous metric for information sets, namely counterfactual regret. Informally, the counterfactual regret of an action $a$ at an information set $I$ is the utility loss or gain from taking $a$ at $I$ provided that $I$ is reached. Formally, define the counterfactual utility $u_i(\sigma, I)$ as the expected utility conditioned on $I$ being reached, with all players playing according to $\sigma$ except for player $i$ who plays in order to reach $I$. Then the counterfactual regret of an action $a$ is defined as: $$ R_i(I, a) = \pi_{-i}^{\sigma}(I)(u_i(\sigma_{I\rightarrow a}, I) - u_i(\sigma, I)) $$ where $\sigma_{I \rightarrow a}$ is a strategy where player $i$ follows $\sigma$ except at $I$, where they always take action $a$. CFR then selects actions at a specfic information set with frequences proportional to their counterfactual regret at that information set. The reason this is useful is because the total counterfactual regret across all information sets serves as an upper bound to the total (non-counterfactual) regret. Since the CFR algorithm generates sublinear counterfactual regret growth, the average strategy yielded converges to a Nash Equilibrium as in vanilla Regret Matching.

Chance Sampling and Monte Carlo CFR#

Even the vanilla CFR algorithm is too computationally inefficient to use in large size extensive games, as calculating the counterfactual utilities still requires traversing the entire game tree. To circumvent this, implementations of CFR for solving Poker commonly estimate the counterfactual utilities by sampling a subset of terminal histories for each information set. This creates a common dynamic for machine learning optimization procedures (e.g. in Stochastic vs Batch gradient descent) where smaller samples increase the speed of iteration but decrease the speed of convergence due to noisier estimates. At the extreme end is Monte Carlo CFR, where only a single terminal history is used at each iteration.

References#

[1] Lanctot, M., Waugh, K., Zinkevich, M., & Bowling, M. (2009). Monte Carlo Sampling for Regret Minimization in Extensive Games. Neural Information Processing Systems, 22, 1078–1086. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3319s48q

[2] Martin J., O. (2022). Course In Game Theory (1st ed.). Phi.

[3] Sandholm, T. (2015). Abstraction for Solving Large Incomplete-Information Games. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v29i1.9757

[4] Zinkevich, M., Johanson, M., Bowling, M., & Piccione, C. (2007). Regret Minimization in Games with Incomplete Information. Neural Information Processing Systems, 20, 1729–1736. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3q23r282